Moroccan genealogical research is complex, almost impossible if one does not speak Arabic. Indeed, apart from the recent period, the documents available will be in Arabic, when they exist. There is a lot of oral tradition too.

The name system is very different and the same individual can be called in several ways, either according to the people who speak about him or according to nicknames that evolve over time.

As soon as we go back to the 19th century, the borders are no lоngеr the same. The colonisation of Algeria by France separated families and tribes into different administrative domains, and scattered sources, as did the different treatment of civil status records after decolonisation.

Finally, oral tradition remains important. It can be very reliable, because that’s how people lived, but you have to find the right person, the right source, and that’s difficult when you’ve moved away from your roots.

Moroccans’ “family names”

When we talk about genealogy, we talk about identifying people, and therefore what we call “family name”. This is the first difficulty: the modern family name was introduced very recently. It simplifies the traditional name and, paradoxically, makes confusion easier.

Switching to a family name, transcription…

The family name is one thing. The French have been slow to impose it. And even if it is written on the card, one can continue to be Mohamed Ben Ichou Ben Youssef Ben Moha. Women kept their maiden names, they were always “daughters of” before being “wives of”.

Finally, the transcription of Arabic names is often problematic, and can be a source of errors, even today.

For example, my husband’s first name is spelled differently in Arabic and in French! Bilal ( بلال ) in Arabic and Blal in French.

But without going that far, which is clearly a transcription error, names can have a slightly different spelling in the Arabic and Latin versions: the street Mohamed Diouri, in Casablanca, is in Arabic rue Mohamed ad-Diouri ( الديوري محمد ) and it appears with this spelling on the street sign, but without the “ad” on the maps, while the corresponding tram station is indeed, in “French”, Mohamed Diouri.

From Berber to Arabic to “Latin spelling”

The icing on the msemmem is the Arabic transcription of Berber names.

These are small details, of course, but they add complexity, especially in a culture where the “name” is much more complex than the first name + family name in the West.

The Moroccan ‘name’: a classical Arabic name

Before civil status, Muslims did not have a family name in the sense that it is used today, but a set of qualifiers that is still used in many countries: just think of the names of the leaders of the Gulf; Mohamed Ben Salmane, is actually called Mohammed ben Salmane ben Abdelaziz Al Saoud

Classical Arabic names are broken down into five parts, traditionally listed in order1 :

- The nіскnаmе or kunya ( كنية ): abu, father of or ‘umm, mother of, followed by the Arabic first name of the eldest child (normally the son, but there are also many cases of a daughter’s name), or pseudonym often omitted in official civil registrations; it corresponds to the customary name. We thus arrive at names whose structure can be “Father of Mohamed son of Hasan”. When a kunya is used, the name can be deleted (to avoid sentences like “Aisha mother of Mohamed daughter of Hasan”)… or not.

- The name or ism ( إسم ): indispensable, corresponds to the our first nаmе. It can be an adjective, a concrete or abstract noun or a verb. In this example, it is Mohamed.

- Patrilineal filiation or nasab ( نسب ): ben, son of, followed by the father’s Arabic first name; filiation may be repeated to the forefathers but is often limited to the father alone. Here, in the case of a dynasty, it is “ben Salmane ben Abdelaziz”. In Europe, this filiation is used in Russian names (in “middle name”) or as a family name in Iceland.

- The origin or nisba ( نسبة ) : demonym, often omitted. Al Saud here. It is the name of a place or a tribe, knowing that many place names are also names of tribes: the M’Goun massif and the M’gouna for example. In the establishment of civil status, the nisba will often be taken as a family name. It is therefore invaluable for genealogical research.

- The honorific name or laqab ( لقب ) : corresponds to the nickname, which often became in modern times an official family name, not always present but generally recommended to qualify the (pre)name. It is the “El Mansour” ( المنصور : the victorious) of Yakoub El Mansour.

The important Moroccan “Nisba” (نسبة)

These nisba, then, mark the оrіgіn: usually the name of the tribe, town or province of origin, in the form of a gentilé (so adding -î at the end).

By “Moroccan”, here, we mean those worn by Moroccans. But the history of the country and the many exchanges that have taken place in the Muslim world mean that many of them correspond to other geographical regions.

- al-Andalusî ( الأَنْدَلُسيّ ): the Andalusian.

- al-Fassi ( الفاسي ) : from Fez.

- al-Bukharî ( البخاري ): the native of Bukhara (e.g. the scholar Muhammad al-Bukharî).

- at-Tabarî ( الطبري ): the native of Tabaristan (e.g. the historian Tabari).

- al-Filali ( الفيلالي ) : native of the Tafilalet region in south-eastern Morocco.

- al-Alami ( العلمي ) : from Jbel el Alam, between Larache and Chefchaouen.

- al-Meknassi ( المكناسي ) : from Meknes.

- at-Tamimi ( التميمي ): from the tribe of Banu Tamim, one of the Arab tribes that came to the Maghreb after Islamisation.

- ad-Doukkali ( الدكاةي ): from the Doukkalas region or the Doukkalis tribe (it’s the same… ) , around El Jadida.

Âl or al-? Be careful not to confuse them!

These two prefixes have a totally different meaning.

Âl, as in Âl Saoud ( آل سعود ), means “of the Saoud family”.

Al, most often written in lower case, with a dash as in the nisba list, above, is simply the definite article ‘the’ ( ال ).

The nasab indicates the filiation

The same definite article al- , or ‘ben’, ‘ibn’, ‘aït’ or even ‘ould’ is used in Mauritania. This filiation can be defined in relation to the name of the father, or of a famous ancestor, whom “everyone knows”. And who may, depending on the region, have the same name as another famous ancestor elsewhere…

Princes, princesses, ladies and lords

In Morocco, as in the whole of North Africa, the chorfas (recognised descendants of the Prophet) are accustomed to precede their first name with an honorific title, Sidi or Moulay for men, and Lalla for women.

They are the equivalent of the names “My Lady” and “My Lord” (spelt like this on purpose, as they were used in the past as a sign of respect). The word Lalla comes from the Arabic llal الآل which means “from the family of the Prophet”, and therefore by definition a woman who is respected, even a saint.

Moulay is a title of nobility ( مولايّ ). Sidi rather means “our master”, it is derived from Sayd ( سـيّد ) and gave “The Cid” in the Arab-Andalusian period!

Amir or Amira means prince(s), Malik or Malika king or queen. These are common first names, whereas in Morocco and in the Muslim world in general, Lalla, Moulay and Sidi are reserved for certain families.

But… they can be used as marks of respect without being given names!

Moroccan civil registry

A diversity of situations, in time and space

To sum up, there were three colonial zones in Morocco: the Spanish north, the French part and the Spanish south, which was under a different administrative regime to the north. As colonisation progressed, the civil status of Moroccans evolved.

Thus, during the protectorate, the French gradually set up civil status in their own way. In the big cities, and everywhere for Europeans, it was kept according to our standards, and in French. For Моrоссаnѕ, it is taking longer to set up, people are not used to it, and do not see the point… often the nomads have all the acts recorded during a moussem or a meeting, as in Imilchil, which will be the source of the moussem legend of the lovers of Imilchil.

A number of specificities exist. For Muslims and Jews, marriages are exclusively religious, and could be kept secret (thus not recorded in the civil register) while being valid. However, Europeans must obtain papers from their consulate before they can get married.

For many people, the date of birth is approximate, they remember the year, and record it afterwards, putting the date as January 1st. In the same way, marriages and deaths and even births can be regularised many years later, on the basis of the twelve witnesses required by Islam.

If your ancestors are Moroccan Muslims, this is where it will be most difficult, especially for the older periods (before the 1950s). If you can find out where they came from in Morocco (and it’s not a big city!) you have a chance of connecting to oral tradition.

Otherwise, if those ancestors were not notables, in one way or another, if you can’t get any family history, it’s much, much more difficult.

In Morocco, before the protectorate, there was no “secular” civil status for Moroccans

And there is very little written religious civil status, it was reserved for rich families.

Eventually, there were contracts and inheritances, but these were mostly oral, written records were reserved for rich families. Hence the role of the famous Muslim “twelve witnesses” who, in daily life, replace written acts.

There were also the tax rolls, and for foreigners, the collection of the protection tax, which the dhimmis had to pay (and which was heavier than the tithe from which they were exempt). Finally, for the Jewish community, there are, as everywhere, contracts, synagogue archives, with a certain stability of large families.

Four dates for Moroccan civil status:

- 4 September 1915: dahir establishing (in the French zone) Moroccan civil status, only applicable to pacified zones, in the short term

- 4 December 1963: dahir making declarations of births and deaths compulsory

- 1976: generalisation of civil status

- 2004: prohibition of marriage by “fatiha” (and 2019, prohibition of its regularisation), therefore obligation to register a marriage with the civil status

Where to go to obtain a copy of a civil status record?

The normal route is the commune where the record was drawn up, or the commune of birth.

You can also contact the Ministry of the Interior, where a service centralises civil status data (but I have not managed to find the exact contact).

Finally, in cases of reconstituted civil status, the courts have archives.

What other sources of family history are available?

Many publications in the Bulletin Officiel may provide leads: water rights records, expropriations, drilling permits, competitions and diplomas, appointments, lists of prisoners during the war (via the Red Cross), etc.

However, given all the problems of transcription, and the commonality of some names, these resources can only give clues.

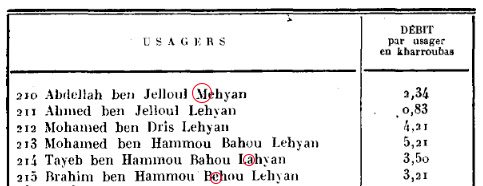

For example, on this record of the water rights of Figuig, mentioned by Youness Khalloufi in his site on the genealogies of Figuig, which has unfortunately disappeared, we can see that there is a Lehyan family and a certain number of holders, the sons of three people, Jelloul, Dris and Hammou Bahou, that Abdellah and Ahmed are brothers, Mohamed, Tayeb and Brahim as well, but we don’t know more. We can оnlу assume that Jelloul, Dris and Hammou are themselves brothers, in reality, given the complexity of these inheritances, they could also be cousins…

I have also circled in red the obvious transcription “errors”, “a” or “e” (which in fact, in Arabic, are almost identical), an “M” which is just the keyboard key to the right of “L”. There are so many of them in six lines that it shows the problems when using texts transcribed in Latin characters.

One can also find “official” family trees in private archives, which were used to prove one’s ancestry. Still on Youness Khalloufi’s website, I found this quote:

The question of the authenticity of the lineage always arises for this type of document. While working on genealogies of noble families in France, I found some rather amusing tricks too. But they remain extremely interesting, and are all the more reliable for recent generations.

And what about women in all this?

Muslim descent is patrilineal. Except in rare cases of famous women from whom it is honourable to descend (such as Sayyida Al Hurra), or of documented inheritances, it will be very difficult to know the mother before the civil status. It may be possible to know the father’s wife, but polygamy makes it impossible to deduce almost automatically that the father’s wife is the mother.

This is also a problem for keeping a Muslim genealogy on a genealogical software, which cannot manage several simultaneous and valid marriages!

So how to tackle a Moroccan genealogy?

Mission difficult does not mean impossible!

But you need to :

- speak and read Arabic and French might be helpful

- be able to access the oral tradition

- be (often) on the spot

More information

- Watiqa : Guichet électronique de commande de documents administratifs - Etat Civil

- Watiqa is the Electronic order desk for administrative documents – Civil Status

The online service that works perfectly, now all the communes are members. It is necessary to have the precise references of the document ordered. Available in French and Arabic only.

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !