For once, we’re not really going to talk about Morocco on this site. But about another country currently in turmoil, Afghanistan.

In 1974, Joseph Kessel published “Le Jeu du Roi” (The King’s Game), a report on the difficult shooting of a documentary in the late 1960s called “Les Cavaliers” (The Horsemen), based on the novel of the same name published in 1967 (this was not the shooting of the Oppenheimer film starring Omar Sharif in 1971).

I’m telling you about it today because the similarity between certain parts of Morocco and Afghanistan has struck me for a long time. And before you cry scandal or accuse me of yo-yoing, others have already noted it. The great writer Tahir Shah, author of The Caliph’s House, is himself of Afghan origin. Raised in London, he recounts in one of his books that his father used to go to Morocco to treat his homesickness.

There are also strong similarities between certain moments in the history of Morocco and Afghanistan. There are many reasons why the two countries have evolved differently, starting with the sea and the opening up to the Mediterranean world, but somehow, a few decades apart, many situations have had important similarities.

There are lots of mountains in Morocco, no plains in Afghanistan

With no coastline neither, Afghanistan is landlocked.

The mountains are a ‘culture’ in themselves.

People who live far apart in the mountains are often closer in their way of life than their fellow citizens on the plains and in the big cities. Morocco’s varied landscapes and its openness to the sea and the world mean that, overall, the country is not comparable to Afghanistan.

But… in the mountainous parts of Morocco, things are a bit different.

I remember crossing the Tichka pass late in the day, looking at the little restaurants lined up on either side of the relatively narrow tarmac road, the rest of the village high above, the cars stopping, the buses dropping off their passengers for a break before continuing the journey to Ouarzazate or Casablanca, the faces of the men, often marked by the hostile conditions, wearing cheche, around a small pot of tea and, perhaps, a tajine of grilled meat, and to find myself transported, all at once, to ” The Horsemen “, to the pass of the Chibar of which the description opens the novel:

The lorries were hardly moving any faster than the camels in the caravans, and the horsemen no faster than the pedestrians. The state of the road forced them to keep the same pace: we were approaching the Chibar, the only gap in the august and monstrous Hindu Kush massif, where, at an altitude of 3,500 metres, all the traffic and all the cartage between southern and northern Afghanistan took place.

On one side, the jagged cliff face. On the other, a bottomless void. Huge ruts and sections of crumbling rock cut the way. The climbs, twists and turns became steeper and steeper, more difficult and dangerous to negotiate.

The caravaneers, muleteers, shepherds and their animals were certainly very tired because of the intense cold and thin air. At least, stuck like lines of ants against the mountain wall, they made their way without risk.

Not the lorries. The road was often so thin that they took up the entire surface and their wheels, along the abyss, bit into the chipped, crumbling edge. A clumsiness, a distraction on the part of the driver, a failure of the engine or brakes threatened to plunge the poorly maintained vehicles, decrepit before their time, into the abyss. Their freight, which always far exceeded the permitted standards, made them even less manoeuvrable on steep slopes.

[…]All the convoys that travelled between the two halves of Afghanistan, separated by the Hindu Kush, stopped off at this predestined spot. There were always dozens of vehicles at a standstill in each direction. Those coming from the south were lined up alongside the torrent, the others against the rock.

On both sides of the platform stretched a very long line of rudimentary inns. These were known as tchaikhanas, because they were mainly used to drink tea, either black or green. The wattle and daub buildings contained only one dark room inside. Outside, there was a terrace under a canopy. This was where the travellers gathered. The cold was fiercer and the breeze crueller. But what man in his right mind would have wanted, for so little, to give up a spectacle such as the arrival of lorries, the disembarkation of passengers, the reunion of friends travelling in the opposite direction.

Admittedly, the Tichka road is wider and in better condition. Of course, the lorries that cross it are not overloaded with passengers on their roofs (but they can take a few…). Of course, many of the vehicles are more luxurious [thanks to tourism]. As for the rest, it’s all the same.

This gallery brings together photos of Afghanistan and Morocco. It’s very easy to tell where you are by paying attention to a few details, but you have to admit that “on the whole” they look very similar!

“Modernisation” is not always “Westernisation”.

It is easy, in Morocco as elsewhere, to be fooled by Western clothes, cars and Coca-Cola. It is dangerous to imagine, as the Americans explicitly did in Afghanistan and Iraq, among other places, that a man in a suit and tie who drinks Coke automatically becomes a convinced liberal capitalist. Afghanistan at the beginning of the twentieth century was more modern than it was in the fifteenth, Japan has modernised while retaining a strong identity, and so on.

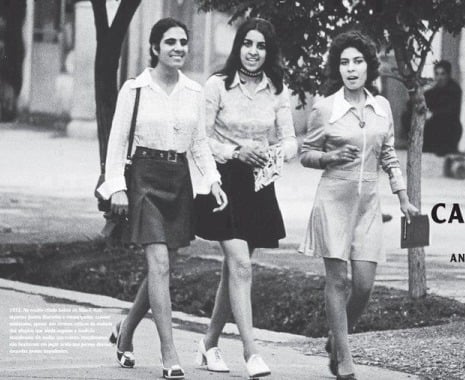

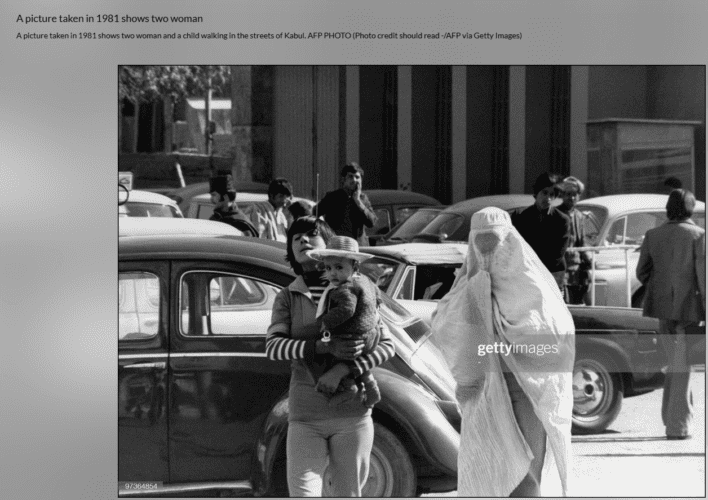

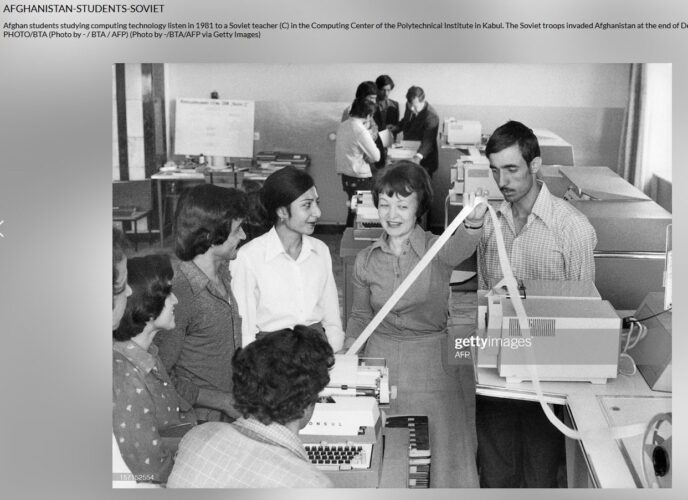

But Afghanistan at the end of the twentieth century was certainly not ‘westernised’ and the few photos circulating on the net of women walking around in short skirts in the Kabul of the 70s and 80s should not be taken for anything other than what they are: the representation of an extremely weak and unrepresentative minority put forward by a communist government which, from the start of its revolution, needed support from abroad and which was not accepted and supported by the majority in the country.

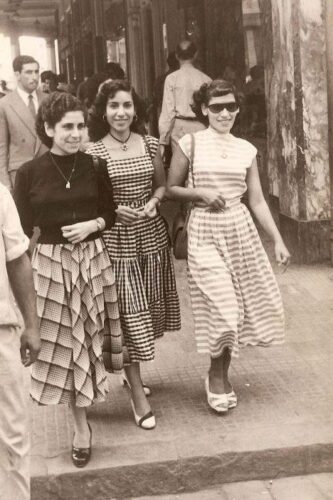

We regularly see the same type of images on Moroccan forums, of women in European clothes in the Casablanca of the 1960s, accompanied by nostalgic comments about a “good time” when women didn’t wear these “horrible Muslim clothes imposed on us from abroad”, with the same bad faith: these photos show a minority of women, either colonists, Jewish Moroccan women, or Moroccan women from high society. But at the same time, the “ordinary” Moroccan woman was veiled.

And above all, whether wearing a djellaba or a caftan, jeans or a suit, veiled or not, bearded or beardless, the overwhelming majority of Moroccans believe that women should arrive at marriage as virgins, even though they now recognise that sexual relations outside marriage are a private matter and that they know many people who practise them. Or, to put it another way, a very small proportion of the population supports the “fast-breakers” (those who want to be able to eat in public during Ramadan).

What these photos tell us

If you take a close look at these photos, which are being shown over and over again, you’ll notice a number of things:

- With one exception, these are women with each other and without men

- “Some of the images show women in chadors and men in traditional dress.

- There’s a complete lack of context

But this context is essential to understanding what is being shown and, consequently, the extent to which these images cannot prove that Afghanistan has been genuinely westernised and destroyed by the evil Taliban.

These photos show what foreigners, most of whom have never been to Afghanistan, or not for a long time, want to see of the country.

Modern Afghan history

To understand Afghanistan a little, you first have to understand the tribes. Like in Morocco. Much more than Morocco, Afghanistan is a country where political life is organised on the basis of tribal affiliation. And according to one tribe in particular, the Pashtuns, who are divided equally between Afghanistan and Pakistan (which is why there were so many Afghan refugees in Pakistan). The political instability of the 20th century is above all linked to the tribal revolts.

This is perhaps the situation Morocco would have been in if the battle against colonisation had not given rise to a national spirit, a Moroccan consciousness that transcended the divisions between Arabs and Berbers that the French wanted. This national cohesion was further strengthened by the Green March. So Morocco is a country where “tribal” belonging is still important, even if it is often hidden behind family ties, but it is not divisive (and this is also partly due to the intelligence of Mohammed VI’s policy and the integration of Amazigh).

Like Iran, with the same results, Afghanistan has undergone forced Westernisation

This is the second very important point in this story. These women were unveiled because of political diktats, not because the population as a whole agreed. Not just anyone can be Atatürk (and contemporary Turkey has indeed been re-Islamised).

Mohammad Zaher Shah, the last Afghan king, reigned from 1933 to 1973, but much of his rule was dominated by his uncles (a bit like Moulay Abdelaziz, who had some serious problems with his brothers Abdelhafid and Youssef, rather like the future Mohammed V, chosen for his rather self-effacing personality, who turned out to be a great king, uniting the whole of Morocco behind him thanks to the exile to Madagascar imposed by the French).

Zaher Shah was a Pashtun, and unlike Mohammed V, he was unable to unite his country above its tribal fractions. In 1945-46, the Hazaras (who were to suffer under the Taliban) revolted against the Pashtunisation of the country’s customs. The fact that the Hazaras were a Shiite minority didn’t help them at all. And since Zaher Shah’s father was murdered by a Hazara… Zaher Shah is Pashtun like Massoud, and like Massoud he went to the French Lycée in Kabul and studied abroad for a long time.

Let’s make it short. Zaher Shah was actually in power for ten years, from 1963 to 1973. At the time, the country was facing a serious economic crisis. On the one hand, things were going badly with Pakistan’s neighbours, and the main trade border was closed.

Zaher Shah is going to do what he can, “but he can’t do much“, as they say on the school reports.

He tried to appeal to foreign powers (the USA and above all the USSR) to obtain economic aid and investment, and to liberalise and modernise his country.

As far as women’s rights were concerned, he made reforms on a slow pace, “chwia chwia”, he encouraged the education of girls and lifted the ban on going out without wearing a veil.

His wife, Humaïra Begum, appeared without a veil, wearing Western clothes. This provoked outraged reactions from traditionalists. Just as a few years ago, the Qatari people took offence at appearances “without a veil” or “with a simple turban showing her hair” by Sheika Moza bint Nasser al-Missned, the wife of the previous Emir. And Moulay Abdelaziz’s reputation was undermined by his “Western” practices, starting with photography.

The first photo, of three young girls in miniskirts, was taken in an upmarket district of Kabul (like Anfa or the Golden Triangle) in 1972. Laurence Brun, the photographer who took it, says

In 1973, a peaceful coup. Thanks mainly to Zaher Shah, who decided to drop the matter.

Mohammad Daoud Khan, a cousin of the king (a sort of Moulay Hicham?) proclaimed the Republic and distanced himself from the Russians.

This great liberal passed a constitution recognising a single party and moving closer to the United States. The latter have absolutely no problem with supporting a vaguely dictatorial regime… But he “could do little” even less than Zaher Shah, and the economic crisis was not getting any better. On the other hand, he continued the policy of providing schooling and education for girls.

In 1978, a communist coup d’état ousted him from power. The USSR was not pleased, but eventually agreed to support the country. Afghanistan then embarked on a form of cooperation reserved for “sister countries”: reforms and monitoring. Alongside agrarian and collectivist reforms and the abolition of peasant debts, the following measures were put in place:

- compulsory schooling for girls

- measures in favour of women’s rights, which tickle the patriarchal structures established in the villages

- once again, the right not to wear the veil

- the right to drive alone

- a stranglehold on higher education and large companies, with ‘development workers’ imposed on the teams, who are there as much to help as to be the eye of Moscow. So yes, 60% of the teaching staff at Kabul University were women, but it was an ‘occupied’ university.

All the other photos of “Westernized” Afghan women date from this period.

Was society generally in agreement? Certainly not, otherwise Islamist resistance would not have been so violent.

And because traditional society was not in tune with these reforms, even under the Communists there was an increase in attacks on women in Western clothing and harassment of working women.

What we forget to mention when we show these Communist propaganda photos of smiling women in suits….

Le Monde’s video on the reality behind the photo of the freed Afghan women

So I urge you, finally, to watch this remarkable video from Le Monde. The newspaper tracked down the author of the photo of the mini-skirts, who is still sorry about the way it was interpreted, and about the fact that this photo was shown to Trump to persuade him that an American presence was all that was needed for Afghanistan to become westernised.

I don’t claim to know Afghanistan because I know Morocco – a little – and I’ve been able to get to know a traditional Morocco that you can lose sight of when you live and work in Casablanca.

Nor do I claim that Afghanistan and Morocco are the same.

But what I do know about Morocco allows me to say that the presentation of an idyllic Afghanistan where women walk around freely in Western clothes is bullshit.

What I know of Morocco allows me to say that clothes don’t make the man, that yes, many Afghan women have traditional clothes that are more colourful and less occulting than the burqua, but that they are certainly subject to the same ‘oppressions’ linked to tradition.

What I know about Morocco and other countries tells me that the West would do better to stop believing in the universalism of its civilisation, and that it should understand that there are several paths to modernity, that the liberation of women depends first and foremost on education and therefore on economic prosperity.

What is happening in Afghanistan today is distressing and terrible. We probably wouldn’t have got to where we are today if it hadn’t been for an uninterrupted succession of Western interventions over the last sixty years, interventions that have been divided between total cynicism and a kind of imbecilic angelism, what I would call ‘civilisation by Coca-Cola’.

And if you want to find out more about Afghanistan, you can subscribe to Tahir Shah’s Facebook account, which regularly posts memories of his various trips to Afghanistan. Or watch this other video

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !