In recent days, a text has appeared explaining that the Statue of Liberty is Moroccan, because during a trip to southern Morocco in 1871, Auguste Bartholdi apparently learnt that the translation of “Amazigh” was “free man/free woman” and decided to crown the Statue of Liberty with an Amazigh crown as a tribute to these free men and, above all, these free women.

It’s a lovely story, but it’s totally false, so I might as well tell you straight away.

On the other hand, it is interesting because it clearly shows the existence of a Mediterranean cultural substratum, with practices and myths that have circulated to such an extent that it is difficult to say with any certainty which country or culture is really at the origin of them. While we know a great deal about Greco-Roman history, we have less first-hand knowledge of the Phoenicians and Carthaginians, as well as Amazigh beliefs and customs, due to a lack of written material.

The Berbers were not the first to populate North Africa, but they have been there for a very long time, “since history” and even before.

Amazigh culture has its own originality, but it was not born in a bubble isolated from all contact with the outside world. In the rituals of Achoura, we find practices from Roman and even Celtic carnivals, and in the “magic of lead”, said to be Arab, we find the chtonian rites practised by the Romans.

Little is known about the Amazigh gods, whose memory has been erased by centuries of monotheism.

All of which is to say that, even if correspondences can be found, as some have done, between a certain type of Berber head jewellery and the Statue of Liberty, in this particular case there is no question of “inspiration” as is claimed, at most a parallel evolution of a common symbolism, most certainly a simple coincidence. The straight line and the square are found everywhere, henna tattoo designs Moroccan designs are close to those drawn in India or Bulgaria, without the one having inspired the other…

But let’s get to the heart of the matter with the photos that would ‘prove’ this pretty story.

A series of photos of Berber women wearing spiked head dresses

The last photo is the most interesting, I think. Like the previous two, it was taken in 2010, in Dakhla, as part of a cultural day at a school, by a Moroccan photographer, ofbado, whose blog you can read here.

2010 ?

The very first mention of the legend of Bartholdi and the Amazigh woman appeared in 2012. So I think it was Abderrahmane Ouali Alami (Ofbado) who unintentionally started this story with his photograph. Because there is a resemblance, of course… but just a coincidence!

So it’s thanks to his photo that a legend has been created.

Now back to the real story…

Bartholdi drew little inspiration from his travels in the Orient

Bartholdi went to the Orient twice, first to Egypt, then to the Red Sea and Yemen, and only a second time to Egypt to present his statue project. “Bartholdi landed in Alexandria on 24 April 1867 and was never to return to the Orient.”

Under the pseudonym of Amilcar Hasenfratz, he produced a number of Orientalist paintings, which can be seen today in the Bartholdi Museum in Colmar. Only one statue by Bartholdi is known, inspired by his trip to Egypt and Yemen: “La Lyre chez les Berbères” (Lyra at the Berbers).

This statue proves three things:

- like all the people of his time, Bartholdi spoke of Berbers, and certainly not of Imazighen or Amazighs; hence made no link with “Freedom”

- like most people of his time, Bartholdi fell prey to a lascivious orientalism that had nothing to do with reality

- although he depicted the Ethiopian lyre (kissar) correctly, he linked it to another culture (there were no Berbers in Ethiopia) and he was not at all struck by the famous silver-tipped headband.

The story of the Statue of Liberty and its inspirations is well known

An initial project for Egypt

During his first trip to Egypt in 1855-1856, Bartholdi was struck by the work being done to open the Suez Canal. He proposed a gigantic project, inspired by the ancient statues of Liberty and the Colossus of Rhodes, of a statue of a woman, dressed as an Egyptian peasant woman and wearing a headband, who would carry a torch and symbolise “Egypt bringing light to Asia” or “Liberty enlightening the East”. The project was rejected by Egypt in 1867 and 1869 because of its cost. It was one of the sources of inspiration for the Statue of Liberty.

The 1870 war and exile in the south of France

An Alsatian, Bartholdi temporarily abandoned his career as a sculptor and fought against the Prussians, even acting as aide-de-camp to Garibaldi, who had come to France’s aid with a corps of volunteers. Once the defeat was confirmed, he went into exile in Aquitaine, and then travelled for several months to the United States.

Travelling in the United States

On 8 June 1871, Bartholdi embarked for New York and spent five months travelling the country to raise funds for his project, the Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World. He made five trips to America in all, the last in 1893.

Columbia, the American “Marianne”

Columbia is a woman, originally an Indian princess, often depicted wearing a crown of feathers, who has come to symbolise the United States. She can also be seen wearing a laurel wreath.

The abandonment of the Phrygian cap in favour of the seven-pointed crown

The seven-pointed crown of laurels is that of the Great Seal of France, created by Jacques-Jean Barre in September 1848. The Phrygian cap, which topped the Egyptian statue designed by Bartholdi, had two disadvantages:

- In the United States, still recovering from the American Civil War, it could be perceived as an abolitionist symbol, since it was the hat worn by freed slaves in Rome. The United States did not want a divisive symbolism.

- It was definitely associated with the French Republic.

The symbol of the seven-pointed crown was well known to Bartholdi, symbolising both :

- the sun (and therefore light, reinforcing the torch to light up the world)

- the seven continents and the seven seas

It was adopted, in agreement with the Americans, without any reference ever being made to “Amazigh freedom” in the exchanges between the various parties concerned.

It remains to be seen whether, despite everything, this story is even plausible?

An Amazigh head jewel, certainly, but atypical

The variety of Amazigh head jewellery is impressive. Nevertheless, most photos, even old ones, show the same type of ornamentation, with variations by tribe or region. On the whole, the text jewellery is made up of headbands and pendants, but they don’t extend too far. One of the reasons for this, I think, is to make it easy to put on the veil… or to load the bales of hay or the heavy burdens that women carry on their heads.

The headband decorated with five silver spikes is only worn by one tribe in Morocco, the Aït Baâmrane. In all the research I’ve been able to do, I’ve only found it on an old photo.

The Aït Baâmrane are a warrior tribe. They are famous for having put up particularly vigorous resistance to Spanish colonisation until 1934. They even regained their independence during the Ifni war, reducing the Spanish occupation to the town of Sidi Ifni and liberating their territory (with the help of the Moroccan army). Like the Aït Atta, on the other side of Morocco. Like the Aït Atta women, the Aït Baâmrane women fight alongside the men.

The Aït Atta women inherited tattoos representing beards. Perhaps this headband also symbolises warrior women?

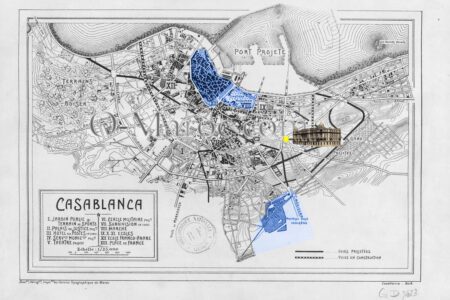

Assuming that Bartholdi’s Amazigh inspiration was real, he would have had to see this headband often enough to consider it typical of Amazigh culture. In other words, he would have had to go to Baâmrane territory, i.e. Sidi Ifni.

A trip to Sidi Ifni Morocco in 1871?

It’s impossible.

First of all, as I said, we know Bartholdi’s schedule and he never went to Morocco.

Secondly, at that time, southern Morocco was a siba country. Getting there wasn’t as simple as getting on a plane for a weekend in Marrakesh. It was a journey that took several months, and had to be prepared well in advance. As did Charles de Foucauld, who stopped much further north, at Tissint, twelve years later, or Vieuchange who went as far as Smara in 1930 – sixty years after Bartholdi’s supposed trip – you had to surround yourself with local guides, disguise yourself to pass for a local. All these things leave traces in a correspondence, in a life, but here, with Auguste Bartholdi, we have nothing.

The territory of the Aït Baamrane in 1871 was not colonised, with one exception, a small enclave granted to Spain for fishing, Sidi Ifni which Spain ‘forgot’.

What need, what interest would Bartholdi have had in going to Sidi Ifni, when his only travels were linked to his projects as a sculptor, to find funds and buyers for his gigantic statues?

The final point

Finally, the last argument to refute the tale is the total absence of results on the web when you search in English for “Bartholdi Amazigh Statue of Liberty” or “Statue of Liberty Berber”, or any other combination.

We can trust our friends on the other side of the Atlantic to know their statue and its history well. If there were a shred of truth in this story, it would have made its way to English-speaking scholars… Especially since Madonna recently made news by wearing this hairstyle at the 2018 MTV Video Music Awards in New York. The debate about cultural appropriation was intense, but once again no one mentioned Bartholdi.

But Berbers aren’t just imazighens, they’re also particularly stubborn, and the Moroccan-inspired Statue of Liberty goat will continue to fly…

By the way… it’s a beautiful statue!

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !