A Berber is defined by his language. A Berber is an Amazigh, the Berber language is Tamazight (in the feminine in the original version). But when a Berber calls out to another Berber, he will call him “oh, Tamazight“, which could be translated as “Oh, you who speak the same language as me”. (Actually, it’s much more complex). So much so that language is at the heart of Berber identity.

And this lаnguаgе is a survivor, almost a miracle, a language that has been (mostly) unwrіttеn for centuries, repressed, considered as a bad language, the language of everyday life, the popular language, as opposed to the beautiful literary language, or the sacred language of the Koran. It is also a language repressed for political reasons, because it is the symbol of an identity claim, that of the Berber peoples.

And yet Berber is still spoken, despite the reduction of Berber-speaking ‘pockets’, despite the absence of a codified grammar, despite the absence of a modern and complete dictionary, despite the divergence of its dialects, of which only Kabyle has really been recorded by Charles de Foucault, Despite the obligation to speak other languages to work, to pray, to succeed, despite the decrees forbidding its use, its transcription, despite the confinement of those who are only Berber-speaking in an often miserable ghetto, Berber is still spoken, sung, rhymed. It is beginning to be written, to be found on the net, to be learned at school, to be heard on television.

To understand the miracle that this survival and vitality of the language represents, we need only compare it with the death of regional languages in most of the European countries (and the revival of some of them, like Welsh or Scottish in England, Breton, Basque or Corse in France).

Amazigh, Darija and standard Arabic

In North Africa, a Berber-speaking child lеаrnѕ his or her mother tongue, like all children, in the cradle, and often speaks only Berber in the family. Then, between the ages of 4 and 6, the first school, the Koranic school, that of the fquih, where he is made to learn the verses of the Koran by heart. Arabic, and classical Arabic, the one that has not evolved since its codification at the end of the 8th century. A language that is so difficult today that very few speak it, a language that is fixed and whose grammar is a series of exceptions.

To take up our comparison, we would have to imagine a little child from Wales, speaking a Celtic language, and sent to school to learn to read, write and recite by heart in аnсіеnt Latin. And even worse, because at least our little schoolboy could write his Welsh and make a dictionary between his language and Latin.

But Berber “cannot be written”. Or at least it was not written, and this is still the case in a rural population largely illiterate.

Our schoolboy grows up, and he goes to school where he learns standard Arabic, or classical Arabic, the one that is spoken every day in Saudi Arabia, for example, or almost (because there is also dialect there). And he goes out in the street, he goes to buy sweets, for example, or to the doctor. And there he will have to speak Arabic. But be careful, not the Arabic he learns at school, the one that everyone speaks in the street, the popular, everyday Arabic, almost another language, which in Morocco is called darija.

So our Welsh schoolboy, who has learned to read in Latin, finds himself соnfrоntеԁ with people who speak English around him.

But here again, this darija is not written. Because it is not done, because it is not Arabic.

For example, the number two is said in classical Arabic “itnaïn” and in Darija “juj“. But it is always written in the same way. Our schoolboy, seeing the price of prickly pears, at 2 dirhams, will “read” it “juj dirham” but, seeing the name of the Hassan II mosque, will read it “Hassan al Thani” out of respect and because “Al juji” does not exist in darija.

To continue, he watches television and sees Egyptian films, whose Arabic is different from his Darija. It is called Masri.

A bit of a crossroads, between classical and his own second language, as Italian is between French and Latin.

And other foreign languages

Things are not so simple, but at around the age of 9 or 10, he will start to learn French, and then one or two years later English, which are written in a different alphabet.

The difference Ьеtwееn the Latin alphabet and the Arabic alphabet is quite important. The Arabic alphabet is not syllabic, it is an “abjad” where only consonants and long vowels are written (knowing that the same long vowel can in fact be articulated as “a”, “i” or “or”) and moreover the letters change shape according to their place in the word and according to the combinations. As in Hebrew, vocalisation, or the inscription of additional signs to fix the vowels, exists for sacred texts, but is totally absent in everyday texts, newspapers, etc….

And all this time, no one is teaching our schoolboy Berber. He is under no pressure to соntіnuе speaking it, sometimes even the opposite. He has to practice classical Arabic, French and English and do well. In Morocco, French is the second “official” language… In the street, he must also practice Darija. And our schoolboy manages to play with all this, gives up nothing, continues to speak Berber….

In France, a century of centralising schooling by the Republic was enough for other languages to disappear, and the number of real speakers of Basque or Breton is ridiculously low. In Great Britain, the number situation is somehow better but the number of people really proficient in Gaelic, Irish, etc. is quite low.

But Berber has survived, in even worse conditions. In spite of the situation in Morocco never reaching the paroxysms of Algeria, “Berberitude” and insubordination have often been combined. It was until recently forbidden to give a child a Berber nаmе, for example (and some administrations continued to be zealous long after the ‘Basri list’ of acceptable names had been abolished).

In 2011, Amazigh is finally granted official language status

The situation is changing in Morocco, and Berber is gradually gaining the right to be used. Taught in schools to all children (Berber-speaking or Arabic-speaking), spoken on television, where every day news is broadcast in Berber, and even taught on the 2M channel, which broadcasts a short daily programme on the subject, promoted by an official body, the Royal Institute for Amazigh Culture, Berber is being reinstated as a language. It has thus entered the Constitution, Article 5 of which states that

Arabic remains the official language of the State. The State shall work to protect and develop the Arabic language and to promote its use. Similarly, Amazigh is an official language of the State, as a common heritage of all Moroccans without exception.

A language that has entered the modern world, and now has a configured keyboard, UTF coding, fonts… You can see in our links at the bottom of the page some addresses to learn more.

So what is Berber? A Semitic language, like Arabic and Hebrew, whose exact origin is lost, like the Berber settlement of North Africa, in proto-historic times. A language to which Ganche is related (an extinct language formerly spoken in the Canary Islands), and whose territory extends from the north of Morocco to the Egyptian oases in the east, and to a few pockets of Burkina Faso to the south.

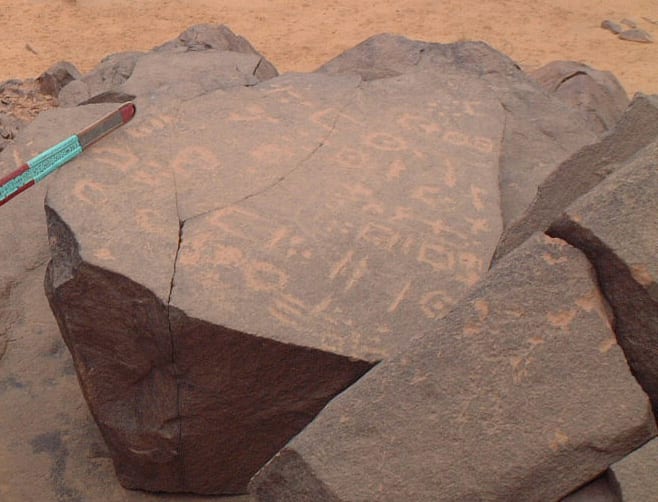

An oral language, whose writing was established late

Morocco is probably the most Berber-speaking of all countries, with an estimated 40-60% 20-25% of the population speaking Berber, divided between several dialects, Rifain or Tarifit in the north, Braber or Tamazight in the High and Middle Atlas, in the centre of the country, Chleuh, or Tachelhit, in the High and Anti Atlas, and Zenet, near the Algerian border. It is estimated that 25-35% of the Algerian population speaks Berber (mainly Kabyle, 4 million speakers, and Chaoui, 2 million speakers). In Tunisia, Berber is mainly spoken in the South. In Libya, about 20% of the population speaks Nefoussa, Tuareg, or Tamasheq, which is spoken throughout the Saharan south, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso and Mauritania.

These are really dialects, and geographical proximity facilitates mutual understanding. An Amazigh and a Chleuh will have no problem unԁеrѕtаnԁіng each other, it will be more difficult between a Kabyle and a Tuareg. But the core of the language remains the same, beyond the variations in vocabulary and pronunciation. A language different from Arabic, even if certain mechanisms (such as the modification of words at the beginning and end, only the central radical remaining constant) are common to Arabic, even if the vocabulary has become inextricably mixed. Many sentences are a mixture of Berber and Arabic words… and French or Spanish words, for all the modern vocabulary, the techniques, the car, the kitchen tools. However, after a few weeks, the ear makes the difference, even if you don’t understand the words, and the very music and sounds of these two languages are different.

How to write Berber?

Berber is therefore a language that is written today.

But how?

In Arabic characters, in Latin characters, in Berber characters, the tifinaghs, which were already used 2,500 years ago before falling into disuse?

And which version of the tіfіnаghѕ? The traditional one, that of the Tuaregs, who use a true abjad (alphabet without vowels), or for example the official transcription in Morocco, known as neo-tifinagh, which includes vowels?

Beyond the linguistic quarrels, often tinged with political claims, which can be found on some Berber forums (is the ‘logic’ of the language closer to Arabic [implied by the oppressor] or to the Latin languages [implied by the coloniser]), the question has gradually been resolved in a practical way.

Since Arabic is only used to write classical Arabic – and not even Darija – it cannot be used for Berber. At the time when the use of tifinaghs was forbidden, the Latin alphabet was used, whose inadequacy in rendering all the particularities of the language became obvious very quickly. The different versions of the transcriptions in neo-Finaghs now make it possible to transcribe these specificities and to avoid the ambiguities of a purely consonantal notation (and incidentally to facilitate the learning of the language by Europeans).

Berber is everywhere in Morocco

When you walk around Morocco, you will speak Berber without knowing it. Names of places and villages are mostly Berber. You should know, for example, that the feminine of a word is always formed by adding a T to the beginning and end of the radical. Tazenakht, Taddart, a small village on the Tichka road, Taroudant, Tiznit… Berber names that dot the map of Morocco, names very often linked to nature, the fig tree, the tree, the well….

You also speak Berber, or rather your grandparents spoke Berber when they called a German a schleuh…. Because the French soldiers who dragged their spats in the dust of the Hamada in pursuit of the insubordinate nomads found their language incomprehensible… just as much as that of the German soldiers whom they faced a few years later in the trenches, and whom they nicknamed like the Berber tribes. Finally, some words, such as “Azur”, come from Berber.

Many Darija words are also directly derived from Berber, ѕtаrtіng with the famous couscous!

Is Berber a barbarian?

Etymologically, a "Berber" is a "barbarian", that is, for the Roman conqueror, all those who did not speak his language. Some people therefore reject the word ‘Berber’ as contemptuous.

This is to forget that the Rоmаnѕ themselves were the barbarians of the Greeks, on the one hand. And above all that they appreciated and admired many of these “barbarians”. In particular, the Visigoths and Ostrogoths, who had settled in the south of Roman Europe, were very refined. The gold, luxury and civilisation of the Visigoths would flourish in Spain, a land that would soon become Moroccan (and Berber) for some centuries.

The Moroccan constitution recognises the place of the Berber language.

Ten years later, what is the situation of Amazigh?

In ten years, things have changed both a lot and little.

In 2016, an organic law on the official character of the Amazigh language was initiated, but, delayed for a long time by the P.J.D. government, it was only voted in 2019, and validated on 5 September 2019 by the Supreme Court.

Although Berber is officially recognised, some caïds continue to refuse Berber first names when registering with the civil registry.

Berber is certainly present on official signs, but some complain that the translations are fanciful, and the official websites very rarely have an Amazigh version.

The role of the I.R.C.A.M. is contested by some, who criticise its choices in terms of transcription, among other things.

Teaching in schools is insufficient to really promote the language.

Berber remains an essential linguistic component of a country that is seeking to move away from the total arabisation of studies and reintroduce a dose of French, seeking, with the development of French and – recently – Chinese, to move away from the influence of the former coloniser, by widening the scope of its possibilities. The promotion of Amazigh has long been at the expense of this linguistic quarrel, whose violence and arbitrary and extreme positions are reminiscent of the French debate on the veil on the other side of the Mediterranean. In one way or another, it is always about an identity…

The dissolution of the IRCAM is on hold

The struggle for Arabisation was manifested through the project to create a National Council for Moroccan Languages and Culture, which would have absorbed the IRCAM, which would have become a mere directorate.

This project caused an outcry in the Amazigh world, and the bill was postponed to another date, which, with the health crisis, the confinement and the economic crisis, will be a long time coming!

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !