It all started on a Facebook group where Sylvie, the author of this article, shared the story of the pirate queen, and we invited her to publish it here. As we talked with her, we realised how fascinating this story was and, upon digging a little deeper, how many questions it raised.

To avoid making this long article too heavy, we have added information on points that we will develop in another article… if you are interested!

Sayyida Al-Hurra: legend or historical reality?

Probably a bit of both. She is undoubtedly a historical figure.

So who was Sayyida Al-Hurra really?

An aristocrat who carries on the legacy of Al-Andalus

The uncertain civil status of a Muslim princess

We do not know for certain the first name of the woman who would become Sayyida Al-Hurra, nor her date or place of birth. Known sources most often refer to her as Aisha or Fatima, with some mentioning Granada in 1485 and others Chefchaouen in 1493. What we do know for certain is her ancestry: she belonged to a prominent family.

Whether Aisha (I choose this name for convenience) was born in Granada or Chefchaouen, she is heir to the history of Al-Andalus, a name encompassing all the territories under Muslim rule that existed on the Iberian Peninsula between 711 (the year Tariq ibn Ziyad set foot on “Jebel Tarik” and began the conquest of Spain) and 1492.

Nostalgia for Al-Andalus

In 1492, the fall of Granada, the last Muslim stronghold on Spanish soil, which had already become a vassal of Spain in 1487, brought an end to the long series of conflicts known collectively as the Reconquista, which had pitted the Christian rulers of the north of the peninsula against the caliphs and emirs of the south for seven centuries. It concluded the last ten years of the “War of Granada”.

In the years leading up to this date, many Arab-Andalusian families gradually returned to Morocco, marked by a sense of loss and uprooting.

This is what happened to Aisha’s family: her father, Sharif Moulay Ali ibn Rashid, was a Muslim nobleman from Andalusia and a member of the Banu Rashid tribe, a branch descended from the Idrissid dynasty ; her mother, Lalla Zahra, née Catherina Fernandez, was a Spanish woman who converted to Islam, originally from the province of Cadiz.

Back in Morocco, Aisha’s parents settled in the Rif Mountains, where Ali ibn Rashid founded the city of Chefchaouen (presumably in 1471, which suggests that Aisha was born there rather than in Granada).

They established a splendid court there, reminiscent of the splendour of Al-Andalus. The kasbah of Chefchaouen was built and designed according to the aesthetic codes of the Alhambra, and it was in this relocated Andalusian setting that Aïcha grew up alongside her brother Ibrahim and her two half-brothers. She received a thorough education from the best teachers of the time.

The young girl learns the secrets of city governance and diplomacy from her father, and Sufi spirituality from the theologian Mohamed ibn Abdallah Al-Ghazwani. Mohamed Al-Ghazwani would later become one of the famous seven saints of Marrakesh.

She is fluent in Arabic, Spanish and Portuguese.

Morocco in turmoil

As young Aïcha completes her education, Morocco finds itself caught up in a double turmoil, both external and internal.

The Andalusian diaspora, spread out between Tetouan on the north coast, the capital Fez, and the Atlantic city of Salé, found Morocco divided between the Watassi dynasty, which held power from its capital Fez, the Sharifs Saadian rivals whose influence was growing in the south of the territory, a few emirates in rebellion against Fez, and a pocket of Portuguese domination on the north coast.

Without a strong central government, Morocco was exposed to Portuguese and Christian colonial incursions, which were then at their peak. Three major cities in northern Morocco were occupied by the Portuguese: Ceuta, Tangier and Asilah. Further south, Safi, Essaouira and Azemmour were or would become “Portuguese cities“, while the Spanish fleet regularly attacked the Moroccan coast.

The greatness of Yakoub Al Mansour’s era has been forgotten; it was not until the arrival of the Alawites that Morocco found itself again.

A first state wedding with the Governor of Tétouan

It was in this turbulent context that Aisha, aged 16 or 18, married the governor of Tétouan, Al-Mandri, who was 30 years her senior. Also of Andalusian origin, Al-Mandri was a close friend of her father’s, whom he joined in the resistance against the Spanish-Portuguese advance.

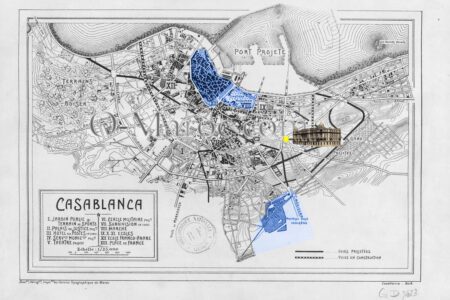

Tétouan was then Morocco’s main port; since the 14th century, it had served as a rear base for frequent military incursions into Andalusia and, in return, suffered Castilian expeditions.

Through this political alliance, the Banou Rashid became major players in Morocco’s unification efforts in the face of the expanding Spanish and Portuguese powers.

Far from fading into the background behind her husband, Aisha supported him and took an active part in the government of Tetouan, to such an extent that when Al-Mandri died in 1515, she succeeded him as governor of Tetouan. It was at this point that she took the name “Sayyida Al-Hurra”, meaning “the free lady”. This was probably a title, which Europeans took to be her real name.

The “pirate queen” … or the corsair governor

Under the leadership of the woman now known as Sayyida Al-Hurra, Tetouan enjoyed 25 years of prosperity, and the Mediterranean trembled!

Tireless, Al-Hurra organised an army, built up an arsenal, sent his fleet to fight the Portuguese on land and at sea, and managed naval traffic within a broader context: the rivalry, across the Mediterranean, between the three empires of Portugal, Spain and the Ottoman Empire, which were engaged in a naval war in which privateering played an important strategic role.

Sayyida Al-Hurra’s fleet participated fully in these activities and quickly became feared by Spanish and Portuguese ships and ports, which it regularly plundered and ransomed.

The passage through Gibraltar is therefore perilous!

Uniting the many private ships engaged in piracy and simultaneously defending the Moroccan coast against Spanish incursions (there was no Moroccan state navy at the time, nor was there a true Moroccan state), Al-Hurra avenged the loss of Granada and earned a well-established reputation as the “pirate queen”.

The spoils of war, along with the ransoms obtained for the release of European prisoners, ensured Tetouan’s prosperity and Sayyida Al-Hurra’s support from her “subjects”.

War, trade and diplomacy

However, and this is where Sayyida Al-Hurra shows the extent of her political wisdom, the “pirate queen” is also an accomplished diplomat, whether negotiating the ransom of her prisoners or trade agreements with Portugal during periods of calm.

As a wise leader, Al-Hurra maintains a balance between war and diplomacy; she defends Morocco’s coastline, its weak point, while forcing European powers to negotiate through the use of hostages.

At the height of its power, it allied itself with the Ottoman corsair leader Khayr ad-Dîn Barbarossa, with whom it plundered the Mediterranean, Barbarossa dominating the East from his forward base in Algiers, and it dominating the West.

Power struggles and palace revolutions

In 1541, the Sultan of Morocco, Ahmed Al-Wattasi, asked for Sayyida Al-Hurra’s hand in marriage. She was then in her fifties.

This marriage was entirely in keeping with the political climate of the time: Al-Wattasi’s position had been weakened by his Saadian rivals, who had defeated him in 1537 at the Battle of Oued El Leben.

The Saadians’ popularity was on the rise, thanks to their victories against the Portuguese. By proposing this marriage to the mistress of Tetouan, the king strengthened his ties with a powerful family (Ibrahim, Al-Hurra’s brother, had already married his sister and had been his minister) and ensured that his coffers would be replenished thanks to the spoils of his wife’s naval campaigns.

Sayyida Al-Hurra accepted, on one condition: for their wedding, the king would travel to Tetouan, thus signalling that she was not relinquishing her position of power through this marriage. This would be the only time in Moroccan history that a royal wedding was not celebrated in Fez.

Unfortunately, the dissensions within the Moroccan dynasties were reflected within the Banu Rashid family. While Al-Hurra and her brother Ibrahim embraced the Watassi party, her half-brother Mohamed preferred the Saadians. Furthermore, the subject of a possible truce with the Portuguese did not meet with unanimous approval: Al-Hurra was fiercely opposed to it, but Ibrahim and the sultan were more open to the idea.

Tensions erupted barely a year after the royal wedding: Sayyida Al-Hurra was overthrown by a member of her own family – sources disagree, sometimes referring to her half-brother, sometimes to her stepson. The bottom line is that the plot ultimately brought an end to the reign of the “free lady”.

The free end of life of the free lady

The story could have ended badly, but once again, Sayyida Al-Hurra demonstrated her wisdom and withdrew to Chefchaouen, her childhood stronghold. She lived there for several years, focusing on spirituality and Sufism, which had permeated her education in her youth, before being driven out again by her political opponents.

She ended her life with her son in Ksar el Kebir, where she died on 14 July 1561. She is buried there, next to Bab Sebta, one of the city gates. Her tomb has since disappeared, but it must have resembled the sanctuary of Lalla Fatima, a saint of the city.

But it is said that she also has a mausoleum in Chefchaouen, in her former home, a building that has now become a place of pilgrimage: the Raïssounia zawyia.

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !