If you’ve read all the questions I have about Yennayer, it’s now time to provide some answers by summarising everything we know about this Berber festival and therefore about the Berber calendar.

Or rather calendars, which can vary from one place to another, from one era to another, or be used in parallel with a lunar calendar and a solar calendar.

How simple is that?

The different Berber calendars

Through various sources, we have :

- an ancient Berber calendar, of which there is ONE mention in a text from the Middle Ages,

- a “Muslim” lunar calendar, but with month names in Amazigh and Muslim and Amazigh festivals,

- and the famous solar “Julian” calendar, starting with Yennayer,

There are very few sources on the pre-Islamic period up to the 18th century. We can only make assumptions based on what we have observed elsewhere in the Berber world, or before modernisation standardised everything:

- The Tuaregs did not identify their years in relation to a given date, but gave them a name corresponding to an event, a characteristic or an amenokal (supreme chief, prince of princes, etc.);

- the Guanches, in the Canary Islands, used a lunar calendar, which began in summer;

- the Egyptians used a solar, “agricultural” calendar, with the start of the year marked by the flooding of the Nile;

- in the Grand Erg Occidental, while some tribes began the year at Yennayer, others chose spring and the time of shearing, when the shepherds were hired; most of them had a year that went from autumn to autumn (Colonel Emile Lefort of the Ylouses).

The different spellings/pronunciations used

Yennayer is a fairly modern way of writing. If you look at older texts (from the 19th and 20th centuries) you will also find Yennaïr, Enaïr, Ennair, Уеnnаr, Nayer, En-Nayer. Admittedly, these are texts written by Westerners, with phonetic transcription rules that have evolved over time.

But these differences also reflect those between the different Amazigh “dialects” (tarifit or rifain, tachelhit or chleuh, tamazight or “amazigh de l’Atlas” in Morocco, taqbaylit or kabyle, tacawit or chaoui in Algeria, tamasheq and its variants among the Tuaregs, tаnfuѕt or nafusi in Libya, etc.).

It is by researching all these spellings on the major historical archive sites that we can gain a better understanding and more information about Yennayer before the Amazigh revival.

The Berber encyclopaedia also mentions the name Haggus and uses Ennayer as its main entry.

What we know about the Berber calendar (ancient)

In reality, very little is known about this calendar, which is thought to have been used before the Romanisation and later the Islamisation of North Africa.

A trace (and only one to date) of the names of the months has been found in a text from the Middle Ages written in Arabic characters, reported by Nico van der Boogert. I had already taken up the names of these months in 2014, and the least we can say is that they are not very clear…

| Number | Name | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | tayyuret temzwarut | First moon |

| 2 | tayyuret tenggwerat | Last moon |

| 3 | yardut | |

| 4 | sinwa | |

| 5 | tasra temzwarut | first herd guarding |

| 6 | tasra tenggwerat | last herd guarding |

| 7 | awdayeɣet yemzwaren | antelope's first offspring |

| 8 | awdayeɣet yenggweran | antelope's last offspring |

| 9 | awzimet yemzwaren | gazelle's first offspring |

| 10 | awzimet yenggweran | gazelle's last offspring |

| 11 | ayssi | |

| 12 | nim |

In this medieval calendar, there seem to be months that refer to breeding and hunting and months that refer to the moon (so it wouldn’t be a solar calendar like the Julian calendar).

The Amazigh lunar and Muslim calendar

There is an Amazigh “lunar” calendar, based on the Hijri year, which gives Amazigh names to the Muslim months without changing their length. But this calendar dates from after the arrival of the Muslims in North Africa.

| Number | Amazigh | Transcription | For the Ayt Merghad (Source Ahmed Skounti) | Others (Source Mohammed Hamam) | Hijri months (details here) | Arabic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ⵄⴰⵛⵓⵔ | Aachur | taεšurt | Ta’achourt | Muharram | محرم |

| 2 | ⵛⴰⵄⴰⵛⵓⵔ = ⵙⴰⵢⵄⴰⵛⵓⵔ | Chayaachur | wawεšur | Win Lmouloud | Safar | صفر |

| 3 | ⵍⵎⵓⵍⵓⴷ | Lmulud | tirwayin | Eguen Izwarn | Rabi’ al awwal | ربيع الأول |

| 4 | ⵛⴰⵢⵄⵍⵎⵓⵍⵓⴷ | Chayaalmulud | inṭfer | Wissin Iguenyoun | Rabi’ al thani | ربيع التاني |

| 5 | ⵉⴽⵏ | Ikn | ikn | Atfas Amzwar | Jumada al awwal | جمادى الأولى |

| 6 | ⵡⵉⵙ ⵙⵉⵏ ⵉⴽⵏⵉⵡⵏ | Wis sin ikniwn | wissin / ikniwn | Atfas Ikran | Jumada al thani | جماد التانية |

| 7 | ⴰⵢⵢⵓⵔ ⵏ ⵉⴳⵯⵔⵔⴰⵎⵏ | Ayyur n igrramn | buygurramen | Win Iguerramn | Rajab | رجب |

| 8 | ⵜⴰⵍⵜⵢⵓⵔⵜ (ⵛⵄⴱⴰⵏ) | Taltyourt (Šeεban ) | Taltyourt | Taltyourt | Chaabane | شعبان |

| 9 | ⵔⵎⴹⴰⵏ = ⴰⵢⵢⵓⵔ ⵏ ⵓⵥⵓⵎ | Rmdan =Ayyur n uzum | Seeban / remdan | Rmdan | Ramadan | رمضان |

| 10 | ⵍⵄⵉⴷ | Laaid | tessi | Win l’Aïd | Shawwal | شوال |

| 11 | ⴳⵔⵍⵄⵢⴰⴷ | Grlaayad | wawessi | Win Guer La’aïad | Dhu al-qi’da | دو القعدة |

| 12 | ⵜⴰⴼⴰⵙⴽⴰ | Tafaska | tafaska | Win Tafaska | Dhu al-hijja | دو الحجة |

The name of the first month, instead of Muharram, is Achour, which of course refers to Baba Achour and to the festival of Ashura, which was very important in Berber country.

Ahmed Skounti explains that among the Ayt Moghad, the women used the lunar calendar and the men the solar calendar. The tribe therefore used two calendars at the same time. Just as all Moroccans use the Hijri and Gregorian calendars today!

With the exception of Chaabane and Ramadan, the names of the months are in Amazigh and refer to festivals: Tafaska for Aïd el Kebir, Tirwayin for Mouloud (anniversary of the birth of the Prophet) which is the plural of tarwayt, the dish prepared during the festivals, including Yennayer.

I also found the names of these months in a blog written by a resident of El Aderj, near Sefrou, who quotes a song “”-Taltyourt -Rmtan -Laaïd Amziane -Bin Laaïad -Laïd Amkrane -Amaachour -Chaïaa Laachour -Lmouloud -Chaïaa Lmouloud -Ayaou -Gayaou -Bouimarchidane”.

The Amazigh “Julian” calendar

This is the one most commonly used today and was taken into account when the Berber calendar was created.

It consists of twelve months and begins on the morning of Gregorian 13 January (and not 14 January as in the orthodox Julian calendars).

| English | Tifinagh | Transcription | Darija | Tachelhit | Chaoui |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | ⵢⵏⵏⴰⵢⵔ | ynnayr | yennayer | nnayr | yennar |

| February | ⴱⵕⴰⵢⵕ | bRayR | febrayer | brayr | furar |

| March | ⵎⴰⵕⵚ | maRS | mars | mars | meyres |

| April | ⵉⴱⵔⵉⵔ | ibrir | abril | ibrir | brir |

| May | ⵎⴰⵢⵢⵓ | mayyu | mayou | mayyuh | mayu |

| June | ⵢⵓⵏⵢⵓ | yunyu | younyou | yunyu | yunyu |

| July | ⵢⵓⵍⵢⵓⵣ | yulyuz | youlyouz | yulyu | yulyu |

| August | ⵖⵓⵛⵜ | ɣusht | ghucht | ɣuct | ɣuct |

| September | ⵛⵓⵜⴰⵏⴱⵉⵔ | shutanbir | choutanbir | cutanbir | ctember |

| October | ⴽⵟⵓⴱⵕ | kTubR | ouktoubr | kṭuber | ktober |

| November | ⵏⵓⵡⴰⵏⴱⵉⵔ | nuwanbir | nuwanbir | nuwanbir | wanber |

| December | ⴷⵓⵊⴰⵏⴱⵉⵔ | dujanbir | dujanbir | dujanbir | jamber |

Still among the Aït Merghad, Ahmed Skounti indicates that June and July are replaced by two Amazigh words: bulεensert (June) is the month of fumigations to deworm the herds, and July is called bu yizegh, for the heat of summer. Here we have traces of an “agricultural calendar”!

The etymology of Yennayer

Recently, theories have developed that are as fanciful as Bartholdi’s supposed amazigh inspiration for the Statue of Liberty. In different forms, they link “Yennayer” to Yenna, from the verb Ini (to say) and to Yer or Your, moon (Ayour in reality), which would therefore be “the words of the moon, the word of Heaven and therefore the “divine word”. This would justify “the determination of successive religions in North Africa to combat this tradition“. (These quotes come from a text by the Haut Commissariat à l’Amazighité, the Algerian equivalent of Ircam. The history of Amazigh struggles is much harder in this country than in Morocco is clearly expressed here in a rather unhistorical lyricism).

Others have talked about the contraction of Yan (first) and Ayour (moon), the first moon, which does indeed correspond to our old medieval calendar (but with a completely different word) and which would still be strange for a solar calendar.

Bullshit and nonsense, baloney and gibberish.

The names of the months in North Africa are, in both Arabic and Tamazight, the names of the Roman months.

And if ‘Yennayer’ didn’t come from Ianuarius, you’d have to explain to me why on earth all the names of the other months sound like those of the Roman calendar, why on earth only ‘Ennaïr’ would have a different etymology, or what would be the Amazigh etymology of xubrayer or furar, ibrir, etc? (One person has attempted the exercise, but Amazigh anthropologists such as Lahoucine Bouyaakoubi point to the ‘poetry’ of these etymologies).

And finally, why is it that the name of this month, which has strange origins but is thought to be Amazigh, is not to be found at all in our Amazigh calendar of the Middle Ages?

The end of ploughing and the “agricultural calendar”

Yes, the Amazigh calendar is an agricultural calendar. Because in practice, all the ancient calendars were agricultural, because agriculture was the most important division of time, which gave rhythm to everyone’s lives.

But an “agricultural calendar” is always dependent on the weather… and that’s why it took so long in Morocco for the days of the major moussems to be fixed with certainty (we suffered a lot from this in the days of the travel agency, whether it was for the dates moussem in Erfoud or that of the Roses).

Above all, Yennayer is not an “agricultural” festival. Of course, it is linked to the seasons. But it has no specific agricultural significance, taking place at a time when there is no longer any agriculture.

This period is linked to the end of authorised ploughing. To understand, in an agricultural society where a lot of land is collectively owned, where water is strictly managed and distributed between farms (whose plots can be redistributed), equality is important, as is the “right time”: if families plough at the wrong time, there can be land grabbing (oops, I’ve gone overboard) or inefficiency and therefore famine.

The ploughing season is therefore decided by the jemaa, starting in October with the rains that follow the setting of the Pleiades and ending in January, around the time of Yennayer. So go and plough frozen or snow-covered ground…

This period is called “ahellal” (yes, the same root as halal, authorised) and is found, with slightly different dates linked to weather conditions, throughout the Mediterranean basin, in Greece, Rome…

But the most important and auspicious period is the start of ploughing, a symbol of growth and development. It determines the whole year, since it is here that the festivals and days of the week are set (just as the calendars were the occasion for the Romans to set the festivals for the coming month). It therefore ends around Yennayer, depending on local decisions.

What’s more, if it were an “agricultural festival“, it would not be so widespread in the Berber world, which is made up of nomadic pastoralists and sedentary farmers alike, two populations with very different annual rhythms. (See above, the start of the year for Berber nomads in the Grand Erg Occidental).

Yennayer before 1980

The Amazigh calendar as we know it today was created in 1980. But what about Yennayer before that date?

When I searched my sources using the different spellings I indicated at the beginning of the post, I actually found many references to Yennayer, or the “Feast of January”, both in the colonial press of the time and, earlier, in the books of ethnologists and explorers.

And many more of these mentions are in Algeria than in Morocco (and almost none in Tunisia).

I mentioned above the nomads of the Grand Erg Occidental, some of whom start their year with Yennayer. There is also Edmond Destaing’s study of “L’Ennayer by the Beni Snous“, published in 1905 (the Beni Snous are a tribe in western Algeria in the Tlemcen region).

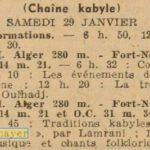

Kabyle traditions are also frequently mentioned.

R. Maunier, in “Les échanges rituels en Afrique du Nord” (Ritual exchanges in North Africa) talks about gift-giving rituals, the taoussa, without limiting it to the Kabyles. He explains that, while waiting to be married, the fiancé must give “expensive” gifts to his future wife, particularly on the occasion of “the feast of January“.

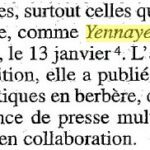

Here are 4 press cuttings, on different dates.

Apart from the celebrations in Ghardaïa in 2006, we’re talking about 12 and 13 January. As for Ghardaïa, I have my doubts as to its accuracy, since they mention Eid El Kebir “at the same time”. In 2006, Eid took place on 30 December…

Yennayer, in a nutshell, and in answer to all my questions…

Yennayer was, even before the creation of the modern Amazigh calendar, a living tradition among Berbers throughout North Africa.

We know almost nothing about the ancient Amazigh calendar, but it is certain that there was never a single calendar.

Its date is clearly linked to the Julian calendar inherited from the Romans, which continued to run alongside the Muslim calendar, but it never marked a new year used throughout the Berber world.

Its rituals are those of a winter passage festival, more linked to propitiatory rites to give oneself good luck in a difficult period when reserves are low than to an agricultural celebration. These are rituals that can be found throughout the Mediterranean area, and even beyond, without it being possible, after so long, to identify what is Amazigh and what is borrowed (and personally, I believe in the universality of the great human myths and rituals, as described by Carl Young in “Man and his Symbols“).

With the revival of Amazigh identity, Yennayer is becoming increasingly important, with some “poets” giving the word and the festival meanings that have nothing to do with history.

It remains to be seen why and how the creation of this modern Amazigh calendar and, above all, why Morocco decided, in one fell swoop, to celebrate 14 January and not 13.

Yennayer existed at the time of Al Andalous

The great Corduan poet Ibn Quzman wrote a text in which he praised

the fragrant atmosphere of the well-stocked souks and depicts the quantities of sweets laid out exclusively to welcome Yennayer.

Was this in Andalusia, or during a trip to the Maghreb? History has no record of him travelling outside the Iberian Peninsula. It is highly likely that the Berber conquerors brought their traditions with them and that these souks were in Spain.

Unlike many poets, Ibn Quzman did not write only in classical Arabic. He used the language of everyday life, and therefore Berber to some extent. His collection, The Diwan, has not been translated into French, but English and Spanish versions are available.

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !

A typo or syntax error? You can select the text and hit Ctrl+Enter to send us a message. Thank you! If this post interested you, maybe you can also leave a comment. We'd love to exchange with you !